There’s a legend about the oak beams that span the dining hall ceiling of New College in Oxford, England. As the story goes, it was discovered in 1859 that the expansive beams would need replacing due to a beetle infestation. The college agonized over where they’d find the oak large enough to replace the beams until a junior fellow suggested that there might be some worthy oaks on the college property scattered across the country.

The college Forrester that maintained the land was summoned and upon inquiry shared that a grove of oaks had been planted to replace the dining hall beams in 1379, the year the college was founded. The plan had been passed down for 500 years between the college foresters, which anticipated the eventual beetle infestation and forbade cutting the oaks down until needed for this very purpose. The Forrester replied by saying, “Well sirs, we was wonderin’ when you’d be askin’”.

Regardless of how factual the legend of the New College oak beams is 1, it conveys something deeper, something intentional. The eventual degradation of the oak beams towering above the dining hall was anticipated at its inception. The land was cleared and an oak grove was planted for the specific purpose of replacing these beams one day in the distant future. Specific people were designated to maintain the grove, who passed down instructions to protect it year after year until the day finally came to cut them down so the oak grove could finally fulfill its purpose.

Think about this story in the context of the digital products that are commonplace today. We have apps to cater to our needs in every variety: ordering a ride, ordering a meal, or streaming an entire season of our favorite show is a few taps away. Goods of any kind can be at our doorstep within 24 hours. We don’t even need to go to the grocery anymore – there’s a service and app for that as well. These products provide convenience at a cost we are willing to accept, but what about their intentionality? Intention requires the foresight to think beyond short-term gain to anticipate long-term consequences. Are any of the products that we use today to make our lives more convenient planting their metaphorical oak grove in anticipation for when things fail or cause inadvertent harm?

Unintentional design

My questioning of the intentionality behind the products we use and take for granted began during rush-hour traffic on a hot summer afternoon as I observed hordes of traffic on my quiet neighborhood street. I later learned that the reason for this was because of Waze, the popular way-finding app well known for its real-time driving directions based on live traffic updates. To save its users a few minutes of commute time, the app was routing them through my neighborhood one after the other. In the process, this converted my street into a congested racetrack which was no longer safe for the children who played there and the pedestrians who walked them. The worst part: there was nothing we could do to stop it.

I remember thinking, “how could Waze be so blatantly dismissive and negligent of my neighborhood?”. It turns out I’m not the only one that feels this way: this app specifically has been cited as the cause for neighborhood streets to become dangerous and congested cut-throughs so users can save some time while ignoring the societal cost it inflicts. Residents are left powerless to stop the algorithm that’s routing impatient commuters through their streets 2. This experience left me wondering how products can intentionally impact people and how little attention we pay to those people during the design process.

Unfortunately, there are many more examples that demonstrate how the products we use can be incredibly negligent, even when they begin with good intentions. Take for example Facebook’s like button, which began as a friendly way to express positivity and soon ushered in a new feedback model that’s now mimicked on every social media platform in some variation. What no one anticipated was how this simple mechanic would mutate into a built-in filter bubble that amplifies the universal tendency towards tribalism 3 and exploits our desire for belonging and social affirmation through tiny dopamine boosts.

Failure to anticipate unintended consequences isn’t isolated to social media. Airbnb has contributed to housing shortages and rent increases by creating a reduced supply as properties shift from serving residents to serving Airbnb users, which hurts residents by raising housing costs 4. Landlords realize they can fetch more on the vacation rental market, resulting in them converting their properties from long-term to short-term rentals. This has shrunk the rental market and therefore pushed prices higher for those living in those areas.

Then there are the electric scooter products like Lyft, Bird, and Lime. These products offer an affordable alternative to ride-sharing or car traffic to make short trips in congested cities. But this convenience it provides for its customers has also led to vandalism, cluttering, and reckless riding 5. The result has been eyesores for cities, obstacles for pedestrians, and a wide range of legislation created on an ad hoc basis.

Failure to anticipate the long-term consequences of design decisions in favor of short-term gain often leads to negligent and sometimes harmful outcomes.

There can also be very real privacy and safety concerns when long-term consequences aren’t adequately considered. Take for example the growing area of personal surveillance products which enable the ability to track, monitor, and quantify activity via video and sound recording, often coupled with facial recognition 6. Consumers that use these products commonly believe they have nothing to fear or hide and so the value they receive is worth the privacy tradeoff. In reality, these products can and have been leveraged against them and others by their employers, the government, their neighbors, stalkers, and domestic abusers.

Even companies that typically emphasize privacy and security can fall into the trap of not thinking through the consequences of the products they’ve designed. Apple’s AirTags are a perfect solution for tracking items of value but their incredible accuracy also makes them an effective stalking tool 7. While the company has announced new anti-stalking features to help address these concerns, the item tracker market is filled with competitors, most of which lack the anti-abuse safeguards that AirTags have.

Failure to anticipate the long-term consequences of design decisions in favor of short-term gain often leads to negligent and sometimes harmful outcomes. When there is no metaphorical oak grove that anticipates when things go awry, there’s no way to adapt or protect those being negatively affected.

Why intention matters

Scenarios where everything is perfectly aligned for a feature or product to work exactly as intended are the path of least resistance. The inconvenient complexities of what might go wrong are pushed to the side or ignored altogether. Our focus becomes the MVP (minimum viable product) while handling edge cases becomes secondary. However, these edge cases seldom get addressed, and more often than not, the MVP becomes the final version. Long-term consequences are ignored over short-term gain, and this is precisely when features and products are set up to negatively impact people.

This begs the question: if a product is negatively impacting people, is it a good product? It boils the problem down to the fundamental question of what ‘good’ design means. I’d argue that good design is that which is intentional and therefore considers long-term consequences over short-term gain. Unfortunately, the drive for speed and innovation more often leads to us optimizing for the ‘happy path’ while ignoring unintended outcomes. Long-term consequences are not entirely included in the common criteria we consider for good design. As a result of our narrow focus on short-term gain, we commonly don’t think to even consider the lasting impact of our design decisions.

When we reexamine the criteria for good design in the context of intentionality, it’s clear this is a missing piece to the dialog around what good design means. Intentionality matters because when it’s ignored, the design becomes irrelevant. We must expand our criteria for what good design is and acknowledge that good design is that which is intentional and therefore considers its long-term impact on both direct and indirect users.

Designing with intentionality

The teams of designers, product managers, and engineers behind the companies I mentioned earlier didn’t set out to create products that negatively affect people; instead, they failed to consider the long-term consequences of their products. Fortunately, there are ways that designers can identify the consequences of our decisions.

Second-order thinking

An effective method for identifying unintentional impact is through second-order thinking. We can take into account how our design will affect indirect users by considering the consequences that will inform our design decisions. Suppose first-order thinking focuses on solving the immediate problem without considering the consequences. In that case, second-order thinking enables us to think through problems in the second, third, or nth order. We activate second-order thinking by asking ourselves “and then what” in a series.

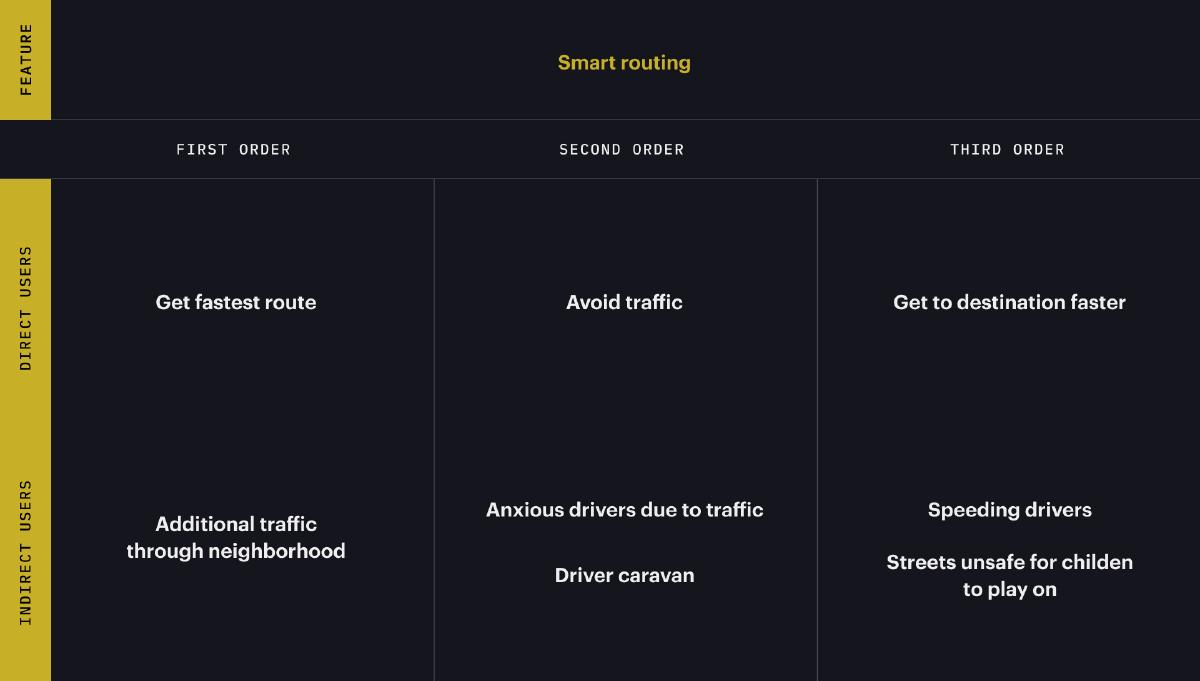

Using Waze as an example, let’s explore how second-order thinking could have helped identify the impact of their product on indirect users. We’ll use the ‘smart routing’ feature of the app as the focus. As you can see, the consequences of the intelligent routing feature for direct users are fairly straightforward. As a result of this feature, these users receive the fastest route, thus avoiding traffic and eventually getting to their destination faster. This scenario is what we’d consider a “happy path”.

Now let’s switch over to our indirect users. The added drivers in their neighborhood are, 1) anxious due to the traffic they seek to avoid, and 2) most likely followed by other drivers also using Waze. The result is speeding drivers and too many cars on the street for it to be safe for the children who live in those neighborhoods. While indirect users aren’t actively engaging with the product, they are still being affected.

Futures Wheel

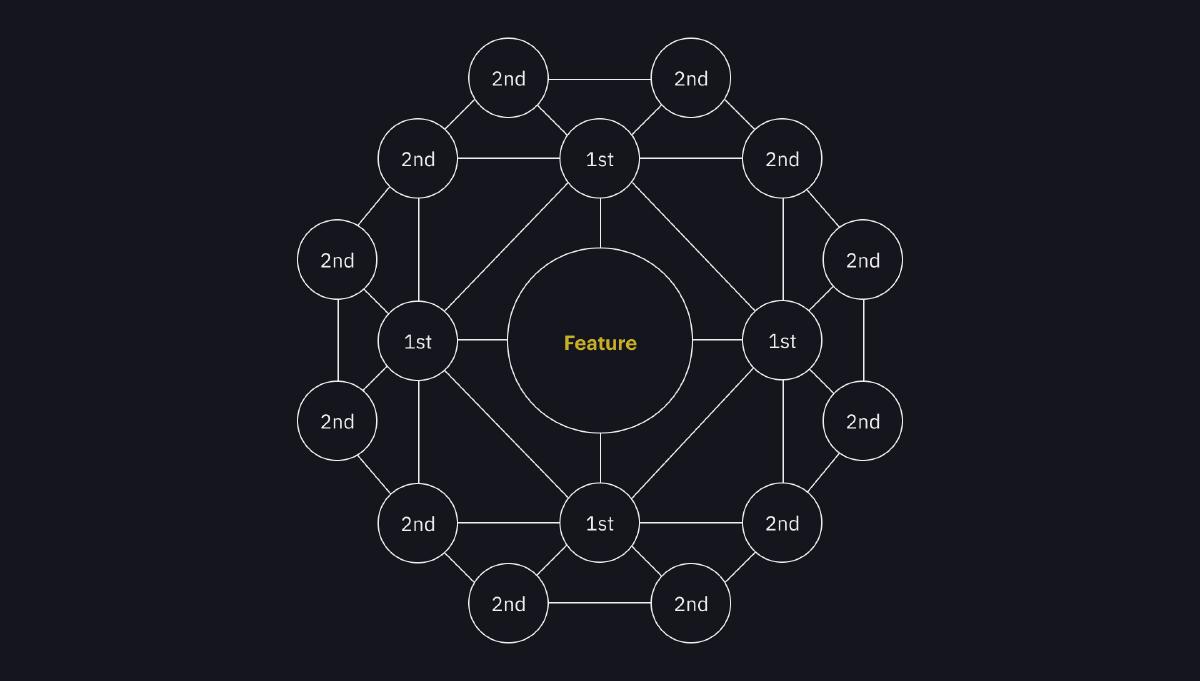

A futures wheel is an exercise created by Jerome C Glenn 8 that enables us to organize thinking and questioning about future development or trend. It’s a structured brainstorm that starts with a root term to evaluate and then events or consequences following directly from that development are positioned around it. Finally, the indirect consequences of the direct consequences are positioned around the first-level consequences. The purpose of this exercise is to understand the possible both direct and indirect impacts and to collect them in a structured format.

Project Pre-mortems

It’s pretty common to run an analysis of a project once the project is over, most often to identify the source of friction or failure that occurred during the project. These sessions, referred to as postmortems or retrospectives, are helpful for teams that wish to improve process and collaboration moving forward but do nothing to identify project risks or consequences at the beginning.

A premortem is the hypothetical opposite of a postmortem in which your team imagines that the project has already failed. It’s a method based on the concept of prospective hindsight: reflecting on a potential future event as if it had already happened. They enable us to visualize the risk or long-term consequences happening in advance and then work backwards to understand how they might be prevented. The final step is to revise an existing project plan with the potential future risks and potential future solutions to those risks.

It’s time we expand what it means to create more meaningful relationships between people and technology by considering the intentionality of the products we build. We can take into account how our design will affect them through methods such as second-order thinking, futures wheel, and post-mortems to identify the consequences to make better product decisions. I believe that in the process of expanding our criteria for what good design is and acknowledging that good design also considers those not directly using the products we build, we’ll create more meaningful relationships between people and technology overall.

-

Siddique, H. (2013). David Cameron’s tale of Oxford college’s trees is a myth, says an academic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/blog/2013/oct/02/david-cameron-oxford-college-trees-myth ↩︎

-

Littman, J. (2019). Waze Hijacked L.A. in the Name of Convenience. Can Anyone Put the Genie Back in the Bottle? Los Angeles Magazine. https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/waze-los-angeles-neighborhoods/ ↩︎

-

Taub, Amanda, and Fisher, Max (2018). Where Countries Are Tinderboxes and Facebook Is a Match. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/21/world/asia/facebook-sri-lanka-riots.html ↩︎

-

Hempel, J. (2018). Airbnb Can’t Win New York—But It Can’t Quit Either. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/airbnb-cant-win-new-yorkbut-it-cant-quit-either ↩︎

-

Gössling, S. (2020). E-scooters – cities should embrace them. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/e-scooters-cities-should-embrace-them-131087 ↩︎

-

Gilliard, C. (2022). The Rise of ‘Luxury Surveillance’. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/10/amazon-tracking-devices-surveillance-state/671772/ ↩︎

-

Chen, Monica and Song, Victoria (2022). Airbags are dangerous — here’s how Apple could fix them. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/3/1/22947917/airtags-privacy-security-stalking-solutions ↩︎

-

Glenn, Jerome. (2021). THE FUTURES WHEEL. Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349335014_THE_FUTURES_WHEEL ↩︎